Rana Foroohar’ın Hayallerindeki Yemek: Ege Kıyısında Bir Ziyafet

Back in the 1970s, my family would often spend summers in Turkey, my father’s home country. An intrepid (not to mention thrifty) traveller, dad’s idea of a good time was to pile the extended family — seven of us, including my grandparents, parents, uncle, brother and me — into his brother’s old Volvo and drive from Istanbul down the Aegean coast, stopping at whichever seaside town or village looked best.

I didn’t relish hours spent riding shotgun in the front seat wedged between dad, the gear shift and my chain-smoking uncle, who would keep the one American cassette tape he owned, Billy Joel’s The Stranger, playing on repeat.

But I did love the places we stayed: tiny family-owned pensions, modest but sweet, often with lovely seaside restaurants that twinkled with fairy lights and smelled of salt and lemons.

One such place, in Assos, a historical village that looks across the Aegean Sea to the Greek Island of Lesbos, is the setting for my fantasy dinner. At dusk, just when the outline of the island begins to fade and dots of lights appear across the water, I gather at a wooden table in front of an old stone inn by the sea with my guests.

Truth be told, I don’t like fancy dinner parties or fancy guests — they stress me out. I’d far rather eat with my family and a few close friends. As I get older, I find myself ruthlessly editing the people I spend time with.

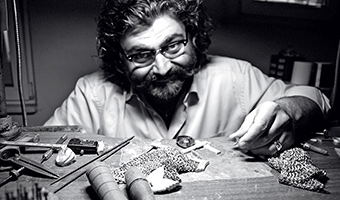

However, given the setting and the needs of this piece, I have invited the writer Orhan Pamuk, who can tell us why Turks are such a melancholy people (his book Istanbul is all about that), and my favourite jeweller, Sevan Bicakci, who spreads out his wares on the table — magical pieces with birds and flowers carved inside precious stones — and lets me choose from among them.

Baris Manco, the late, great Turkish pop singer, can come too and serenade us in his full 1970s Turkish hippie regalia — long black locks, handlebar moustache, kaftan and big silver rings on every finger. The author Jason Goodwin reads to us from his wonderful Lords of the Horizons: A History of the Ottoman Empire. And of course, my dad Aygen Dogar is there, with his backgammon set in tow.

We start the meal with raki, the anise-flavoured liqueur beloved of Turks and Greeks alike, and meze cooked by my grandmother, who passed away several years ago. She makes her trademark borek, delicate cheese-and-parsley-filled tunnels of filo dough fried in olive oil, and kofte, Turkish meatballs blended with breadcrumbs, lots of cumin, onions, salt, pepper and loads of garlic, which she doesn’t chop but crushes into a fine paste with a mortar and pestle.

I help her in the kitchen as I used to. My grandmother didn’t write her recipes down, but would talk them to me, giving instructions along the lines of “the dough for this dumpling should feel like your ear lobe” as she touched her own ear, the armful of gold bracelets that were her dowry dangling as she worked.

Cooking was her pleasure, but she was a tough customer with merchants, so she insists that the son of the innkeeper gets in his boat and goes out to fish for the main course, seafood prepared simply over charcoal with lemon and oil. We have it with warm pita bread dotted with black sesame seeds — crisp and chewy at the same time — and perfectly cooked rice with lots of tomato and butter.

Alongside this, we enjoy my grandmother’s zeytin yagli, a particularly Turkish green-bean dish with tomatoes and onions. She cooks hers slowly, layering onions, tomatoes and beans over and over again in a giant pot, before topping with a few spoons of sugar and salt, and lots of olive oil, then simmering for an hour. The dish is left to cool, and eaten at room temperature or even cold.

All this is enjoyed with plenty of cold Efes Pilsen beer and maybe a nice light Spanish wine — nothing too fancy.

After dinner, it is time to hike up the 235-metre hill that leads to the Temple of Athena at the top of an acropolis that crowns Assos. The structure, which dates back to 530BC, is in remarkably good shape and, as a child, I was amazed that I was allowed to play around it and even pocket a rock or two (thankfully, the place is now protected as a historical site).

The walk is enlivening; at the top of the hill, I unwrap a basket of my grandmother’s honey-syrup cookies (each with a blanched almond in the centre) and individual pots of sutlac, her trademark dessert. Cooking it is an ordeal, but totally worth it. You start with unpasteurised local milk, as fresh from the cow as possible, with plenty of golden cream on top. Into this goes rice and sugar, which is then stirred nonstop for an hour or more, put into bowls, sprinkled with cinnamon and chilled. Some people try to speed things up by using rice flour to thicken it but that would be cheating.

If it were daytime, we might enjoy a three-sided view of Lesbos, Pergamum and Mount Ida in Phrygia. But since it’s evening, we stargaze instead, the perfect end to a fantasy dinner.