Türk Sanatında Tarihin Yansımaları

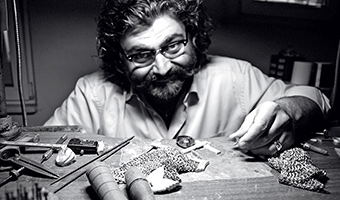

Calling Sevan Bicakci a jeweler is like calling Michelangelo a carver.

From his five-story atelier outside the Grand Bazaar in Istanbul, Mr. Bicakci, a Turk of Armenian descent, works with his team of artisans to create pieces like dome-shaped rings that celebrate the city’s Byzantine and Ottoman heritage.

“I am near the bazaar, the Haghia Sophia, Blue Mosque, Topkapi Palace, Basilica Cistern, Cemberlitas Turkish bath, and, and, and,” he said, listing many of the historical sites in the Old City. “Living my life among all these monuments has inspired me to create a particular style, which is a lot about putting layers on top of each other” — much like the layered history of the Haghia Sophia itself, a Byzantine church turned mosque, turned museum.

“Entering any of them, especially walking through the streets of the Grand Bazaar, makes me feel as if I would be traveling in a time machine,” he said. “This is how I came to contemplate what I do now. I may have walked thousands of such kilometers as a young goldsmith.”

As a youth, like many even today in Turkey, he worked here and there in odd jobs, dropping out of school in the fifth grade and becoming an apprentice to a relative who was a goldsmith. At 18, he opened his own workshop. Now 42, Mr. Bicakci is known internationally thanks to pieces like his Haghia Sophia rings. One, for example, of gold, silver, diamonds and enamel, shows the monument in miniature, seeming to float within a smoky quartz. Another has a platinum and diamond Haghia Sophia set inside a rose quartz cabochon.

He makes them by sculpting translucent gemstones like aquamarines, citrines and even emeralds, using dentists’ tools to carve into the underside of the gems, a slow and painstaking process known as inverse intaglio. The shapes are not always of buildings: A “Lalezar” or Tulip Garden ring features petals engraved inside an amethyst.

The technique can be risky.

“Digging into gemstones from their rear sides makes the work a bigger challenge,” said Emre Dilaver, Mr. Bicakci’s creative director, because it “becomes hard to control the execution quality. At the end of the day, many stones get cracked during the process, or the final execution quality does not satisfy us.”

“That’s exactly where Sevan’s strength is,” Mr. Dilaver added. “He likes challenges and only cares about accomplishing goals in terms of aesthetics, not costs.”

At first glance, this aesthetic doesn’t seem to have much everyday appeal. But, Mr. Bicakci said, “everyday wear is a very relative term. I wear several pieces — rings, bracelets and chains together — in my everyday life without feeling strange at all.”

The people who wear his jewelry are “mostly collectors, small groups of people from diverse parts of the world,” Mr. Bicakci said, “who seem to value pieces with strong statements, rather than just being precious accessories.”

An early fan who has gone on to acquire several pieces is Guler Sabanci, one of the most powerful businesswomen in Europe as the chairwoman and managing director of Sabanci Holding, the parent company of Sabanci Group, the largest industrial and financial conglomerate in Turkey.

“I have discovered Sevan about 12 years ago,’ Ms. Sabanci said by email. “I heard of his collection from a local television program about young talents and visited him at his place near the Grand Bazaar. I was fascinated by his talent, passion and joyful interpretation of Ottoman sultans, which led me to buy two rings: one of Sultan Beyazid and one of Sultan Selim.”

His work, she wrote, contains “an incredible amount of delicacy and aesthetic detail, along with a deep historical and cultural heritage that resonates Byzantine, Ottoman and Istanbul today.”

Mr. Bicakci’s works are sold through his boutiques in Istanbul and Dubai, and at stores like Barneys New York and the Talisman Gallery in London.

“I cannot work on commission,” Mr, Bicakci said, “because of our extremely low capacity to produce. I have barely time to focus on my own ideas.”

The atelier produces only about 500 pieces each year, he said. The rings range in price from about $10,000 to $30,000, and simple chains start at around $3,000. “I do not create for price points,” he said. “The price is calculated once a piece is finished.”

To source his materials, he used to visit gemstone trade shows. “Now, the reputation of my work seems to motivate sources of unusual materials towards contacting me,” he said.

Such materials include anything from bones to diamonds. “I use everything, except for synthetic materials and endangered species,” Mr. Bicakci said.

While jewelry workshops usually specialize in a single activity such as metal-working or gemstone setting, he said, “my atelier may be unique in combining all of those aspects of jewelry making with the fine arts disciplines, such as painting, sculpture, calligraphy, and micro-mosaic setting.”

At the entrance, there is a “kind of a showroom with a library, some showcases and two small rooms in the back part, where visitors can view collections of currently available work,” he said. And a large part of his space is dedicated to what he calls “just experimenting.”

With a creative core of more than 10 people, “I keep walking up and down the floors and between all workbenches in order to supervise production,” he said.

“The process starts with story-telling and continues with making sketches accordingly, which get edited until they become detailed drawings,” he explained. “Improvisations are inevitable in many cases as I discover that certain targets prove to be Mission Impossible.”

“Although it is not always easy to keep strong egos working together, enthusiasm is our most important ingredient,” he added. “The results have been worth all headaches so far.”

Mr. Bicakci’s techniques have grown more sophisticated over the years. “Learning by doing has helped our skills to evolve,” he said. “As a result, the intaglios, for example, are much deeper, much more three-dimensional and colorful today. I can also afford to use more precious materials now.”

While he is best known for his spectacular rings, Istanbul is not his only inspiration. Many of the pieces by Mr. Bicakci, whose surname means blade smith in Turkish, feature a stylized dagger.

He has also created pendants with a padlock theme, like his Treasure Chest of gold, silver and dozens of diamonds. These locks, he said, are inspired by “an old and unfortunately dying tradition of probably Iranian origin: Grandmas, going to mausoleums of holy fathers to pray for God’s mercy and to wish for good things to happen to their loved ones, used to put padlocks on fences enclosing the grave. The padlock symbolized their promise to do a charitable act in return,” such as giving food or clothing to the less fortunate.

Other motifs include goddesses, fruits or even insects. He has made, for example a starfish-shaped ring of gold, silver and pink sapphires, and a spider-shaped ring using gold, silver, diamonds and a large pearl.

He also recently teamed with the luxury publisher Assouline for a book about his life and works. “The idea excited me,” he said, “especially because of its promise to make my work understood to readers who have never been to Istanbul. They will hopefully desire to visit my country more after reading it.”

In New York last month for a book signing at Sotheby’s, Mr. Bicakci said by email that he planned to focus on watches when he returned to Istanbul.

“Work on the idea had begun five years ago and the first fruits are coming out just now,” he said. “I want to be able to do an exhibition with 25 to 30 watches by this time next year.”